This is a Guest Post by Tony Buzbee

Everyone agrees Houston has a flooding problem. There has been much talk about it, but very little has been done. Indeed, Houston’s own “Flood Czar” admits we are in no better condition to face the next storm than we were before Hurricane Harvey. We have to get serious. Did you know that when the current mayor came into office, his transition team laid out multiple, tangible things that could be done to eliminate or at least mitigate the impact of flooding? Almost none were accomplished. We need to be aggressive and realistic. It’s time to do something.

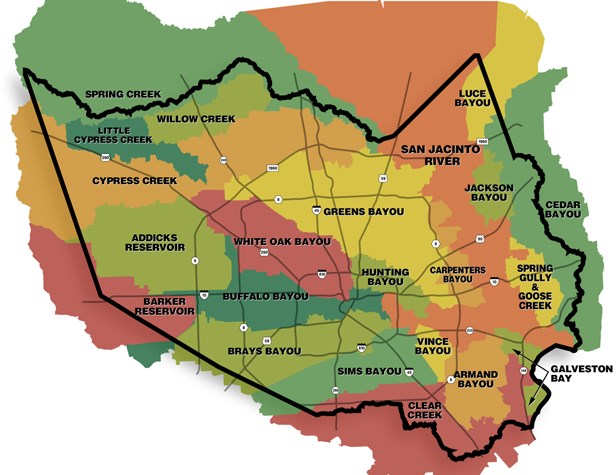

We must remember that the flooding issue is different all across the city. In Kingwood, for example, there are very specific issues with regard to the need for immediate and complete dredging of the Mouth Bar and thereafter scheduled maintenance dredging; pushing sand miners away from the river and holding them accountable when they break the rules; and the installation of flood gates in Lake Houston to properly control the water releases. When we discuss the west side of town, of course, the issues are different. There are major capacity issues with regard to the Barker’s and Addick’s reservoirs and there are issues with the strength of the levees; the residents need to know when the flood gates are opened; building within the planned reservoir runoff should be forbidden; and there is a need for a third detention area. Of course, Meyerland is yet another area that has unique issues with regard to flooding, requiring a unique solution, some of which are discussed herein.

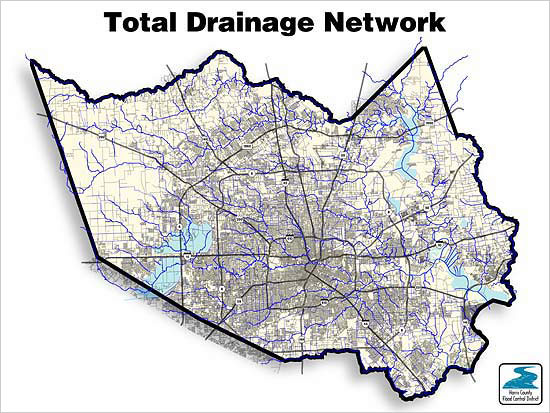

Setting aside the specific issues that are unique to some parts of the city, we face three distinct threats from flooding – storm surge, river flooding, and sheet flow (the technical name for street flooding.) While we aren’t going to be able to fix the problems overnight, the city can work together with the business community to achieve long term improvement in short order.

To begin with, it’s important to understand the different nature of the three types of flooding. Storm surge flooding comes with hurricanes. It’s big and scary; it’s also very predictable. The contours of storm surge flooding are well defined. The National Hurricane Center publishes maps of the Sea, Lake and Overland Surges from Hurricanes (SLOSH). Within the SLOSH modeling, they produce a Maximum of Maximums map (MoM.) This map is the absolute worst-case scenario. Looking at the worst-case scenario tells us just how bad things can get, but also tells us the small scope of danger. The human loss and suffering are significant and need to be mitigated, but, thankfully, the total population exposed to danger is small when looking at the city as a whole.

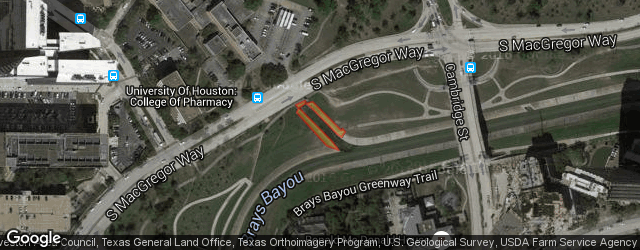

River flooding is what causes our bayous to overflow and brings misery to the city. This is in part determined by the upstream flow, and partly determined by the amount of rain falling in and near the city. Addressing this problem requires looking at both elements of the problem. What can we do when the big surge of water moves to the city, and what can we do to try and keep rain that falls near and in the city from causing the waterways to overflow?

Sheet flow is a different threat. No one is safe from sheet flow, and sheet flow issues exacerbate river flooding issues if not dealt with appropriately. The mismanagement of sheet flow impacts all of us, and we must address this problem in order to both protect homes as well as reign in costs to mitigating the river flooding issues we face.

It’s easy to envision storm surge and river flooding, but when someone says sheet flow that doesn’t bring an image to mind. So, what is sheet flow? Sheet flow is the technical name to how water moves when it is not in a defined channel – like a river or bayou. Sheet flow is what causes street flooding. Sheet flow running into the bayous is what leads to river flooding. We can’t stop the sheet flow upstream from causing us problems, but we can, and must, address sheet flow issues in the city to protect homes, minimize traffic and economic disruption, and lessen the impacts from river flooding.

The rain this May in Kingwood is a good example of the disaster than can happen when sheet flow is not handled properly. This recent flooding, which severely impacted the Elm Grove neighborhood and others, was the result of a developer who failed to follow the rules. That developer, when clearing and preparing for development, caused slopes that directly impacted the surrounding neighborhoods, with no preparation for that impact. But, sheet flow isn’t just something that impacts communities due to errant developers. Street flooding from sheet flow happens when the amount of water trying to enter into the storm drainage system overwhelms the drainage capacity. The water then backs up into yards and eventually into houses.

Hydrologists and engineers have a formula to explain sheet flow, but in simple terms the variable called the “S curve” is what determines how bad sheet flow issues are. The S curve is a measurement of how much and how fast water flows over the surface. When rain falls, some is absorbed into the ground, and some flows into the storm drainage system. The S curve tells us how much, and how fast, the water enters the storm drainage system. When rain falls, some falls onto grass, some falls into ditches, and some falls into the concrete jungle. Grass is better for flow control than ditches, and ditches are better than the curb and gutter system that lines many of our streets.

This problem can be addressed in two ways – improving the storm drainage system’s capability to handle sheet flow and reducing the amount and speed in which water is added into the system. We can address both issues easily; it’s just a matter of having the political will and financial discipline to make the needed changes.

To begin with, we are paying a drainage fee and an accompanying ad valorem tax, and we need to make sure that they are being used only for the intended flood control purpose that was promised when the voters approved the tax. The drainage fee was approved under the premise that it would be used to fund drainage improvements and pay down past drainage debt. These should be the only items on which these funds are spent. Even then, we need to focus on actions that will have an immediate impact on sheet flow control over paying down debt.

Long term planning and project completion are necessary for some aspects of flood control. However, we also can act on items that will immediately improve the situation. The storm drainage system has deteriorated, resulting in lost capacity. Identifying areas where the storm drainage system has structural damage and areas where the drainage system has become clogged will lead to an immediate increase in capacity. Just like a slow draining sink or bathtub, if you can clear the plug, the water drains faster. Making these repairs and unplugging the clogs increases the drainage capacity, getting water off our streets faster. This is actually simple stuff, if we had a leader who focused on it and aggressively but methodically addressed it.

Draining the streets faster helps lessen the extent and duration of flooding, but it doesn’t do anything to prevent flooding in the first place. An effective sheet flow flood control program must address both drainage as well as prevention. To that end, the city needs to work with local citizens and businesses to reduce the amount of water that is going into the storm drainage system in the first place. When elected mayor, I will push the city to take the following steps:

1) When a business makes improvements, any proposal that includes flood abatement as a part of the design can be made as a line item in the proposal during the permitting process. Any amount line itemed and spent on flood mitigation activities will receive a dollar for dollar reduction in drainage taxes the year the flood mitigation improvement occurs.

2) I will direct our permitting process to give priority to identifying and approving improvements where the total amount spent on flood mitigation is at least 15% of the cost of the project. These improvements will be brought to the front of the line for approval.

3) Since replacing concrete with natural surfaces both absorbs more rainfall, and slows the speed in which water flows into the storm drainage system, we will implement a Beautify Houston program where businesses can be recommended for judging and the city will select one business a month for recognition of their effort to beautify their property.

Houston is full of citizens who care about the city. I’ve heard stories of people walking the neighborhoods during Hurricane Harvey and clearing debris from gutters so that water could again flow freely into the storm drainage system. We will re-establish the adopt a drain program since many drains remain “unadopted”. Not only will we make a push to have every drain adopted, but we will specifically recognize individuals and businesses who are participating in the program. On the city’s web page, we will specifically make a link listing every business or individual who has adopted a drain, and if they have a web page we will link to it. We have the citizens ready to assist; it’s just a matter of promoting the need and giving recognition to those who step up to address the problem.

Simply demanding accountability for how the drainage fee is spent, focusing on actions that have an immediate impact, and engaging with businesses and individuals who want to be part of the solution will improve our sheet flow issues. However, sheet flow is only one area that we need to address. The bigger issues of river flooding and storm surge protection need to be addressed as well.

The larger expenditures of river flooding and storm surge control are a much more expensive proposition. In these areas, we need to look at the success that the county has had with flood control measures. To begin with, we need to drive down the time it takes to implement flood mitigation. The best plans are worthless if they are never implemented. One of the biggest factors in the delay is the city currently operates under a bond method. We must have the cash on hand before work begins. It’s time to recognize we have a stable funding source – the drainage fee – and change the way we operate for funding these projects. We were promised “pay as you go” when we voted for the drainage fee. We need to shift to “pay as you go” operations to begin and complete projects in a timely manner. Rather than 5 to 8 year projects, since we have a funding source that is “pay as you go,” we should be accomplishing drainage projects in a 1 to 3 year time span. We have to change the way we are thinking about these projects.

The requirement to have the cash on hand not only needlessly delays the initiation of projects, but it also allows the city to indefinitely forgo some of the expensive needed projects by directing expenditures in a manner that never allows for the required cash on hand to accumulate. Rather than simply deny the project, the city can say that they want to help but that the funds simply aren’t available. The city can kill a project without ever actually declaring they do not want to do the project. Switching to a “pay as you go” method not only allows the city to begin projects that currently cannot take place, but it holds the city accountable for all proposed projects rather than allowing the city to kill a project by indefinite inaction.

We must also take care to strengthen our relationship with the Harris County Flood Control District and the Army Corps of Engineers. Some projects are simply beyond the reach of the city. We cannot do anything about rainfall upstream of the city. However, the HCFCD and COE can, and we need to work with them as a team to make certain we have an integrated plan on how to address upstream issues. This requires cooperation, and at times compromise, in order to achieve the desired end results. Working together with HCFCD and COE also leads to efficiencies from economies of scale. Integrated cooperation means that the planning and required environmental impact assessment can be divided between the city, HCFCD and COE. Working together to plan and cut through the administrative red tape not only reduces cost, but also speeds up when work can begin.

Lastly, we need to invigorate thinking in flood control processes. The city is blessed to have some of the best and brightest minds working in the private sector. We need to invite people with geology, engineering, hydrology, and meteorology backgrounds into a volunteer committee to inject fresh ideas into the flood control process. To that end, when elected mayor I will solicit volunteers from the private sector to form a select committee on flood control to offer ideas on how to address the issues we face. The committee will have access to public works information and individuals, but they will report to me, not public works, on what they believe to be the best course of action to take regarding flood control. This is not a condemnation of public works, but rather an acknowledgment that “group think” can set in when an organization has become well established and committed to a course of action. The goal of the select committee is to offer ideas to invigorate the process, rather than continue with the “group think” and management by inertia that can set in with large time-consuming projects.

In the midst of evacuations and rescues, the meeting began after 9 a.m. Councilmembers Travis and Martin were not present as they tried to help their districts in this tragedy. The true purpose of this meeting was for councilmembers to praise Turner’s handling of Harvey relief efforts. Turner allowed each councilmember to tell stories of Turner’s good works. Turner’s audience was Senator Ted Cruz and Congresswoman Sheila Jackson Lee because Turner wants them to bring home the bacon for the crooked contractors.

In the midst of evacuations and rescues, the meeting began after 9 a.m. Councilmembers Travis and Martin were not present as they tried to help their districts in this tragedy. The true purpose of this meeting was for councilmembers to praise Turner’s handling of Harvey relief efforts. Turner allowed each councilmember to tell stories of Turner’s good works. Turner’s audience was Senator Ted Cruz and Congresswoman Sheila Jackson Lee because Turner wants them to bring home the bacon for the crooked contractors. Turner and his friends. Then, SheJack hugged Cruz. Hopefully, Cruz sees through this bologna.

Turner and his friends. Then, SheJack hugged Cruz. Hopefully, Cruz sees through this bologna.