Review: Jack Kemp by Mort Kondracke and Fred Barnes

By Steve Parkhurst

Finally! It may have taken six and a half years after his passing, but there is finally a book decidedly about Jack Kemp. Due for release in bookstores and online this coming Tuesday, Jack Kemp: The Bleeding-Heart Conservative Who Changed America by Mort Kondracke and Fred Barnes, offers readers a fresh recap of the life of “the most important politician of the twentieth century who was not President.” A sentiment I agree with fully.

Any reader of Big Jolly Politics knows of the regular mentions of Jack Kemp on this website, primarily by Ed Hubbard and myself, but not limited to the two of us.

While Jack Kemp is not an authorized biography, this is the first attempt to explain a man and his legacy that deserves understanding and studying. Jack Kemp is well documented and it reads fairly well as it never gets bogged down in mush the way some political narratives can.

The authors rely on news reports of the day and official documents to back up plenty of fresh interviews with those who worked with Jack Kemp over the course of his days as a football player, a Congressman, a Presidential candidate, a Vice-Presidential candidate and finally as a think tank entrepreneur.

Kondracke and Barnes spend a lot of time weaving their way through the two biggest domestic legislative accomplishments of the Ronald Reagan presidency: the Economic Recovery and Tax Act of 1981 and the Tax Reform Act of 1986. Jack Kemp was crucial and necessary to both.

The supply-side economics which were the basis of the large tax rate cuts voted and signed into law in 1981 are but one part of the success story. The 1986 Tax Reform Act was at least equally as important, though seemingly less talked about in political writing. Much has been written about the supply-side economics movement on the 1970s and 1980s, but the 1986 story is told less often.

Both stories are shared in Jack Kemp in great detail, with Jack Kemp not necessarily playing the hero, but showing true leadership, much of it based purely on principle. And readers are offered a play-by-play for both, and for good reason.

The twenty-five years of prosperity that the tax rate cuts engineered are impossible to argue against, though many on the Left are still trying to debunk. And the tax reform was so monumental it garnered “the largest audience for a bill signing during the Reagan presidency.” And as Kondracke and Barnes note, “Reagan called the measure “the best anti-poverty bill, the best pro-family measure, the best job-creation program ever to come out of the Congress of the United States.”

The authors also editorialized, “The 1986 tax reform stands even now as a model for leaders of both parties who hope to make the tax code simpler, fairer, and more economically efficient.” Reading Jack Kemp makes this statement clearer, and valid.

These were stories worth reading. For some, the play-by-play will be too much minutiae to digest. For students or researchers, there can never be enough. It is a fine line to tread with a book such as this. Congressional and policy battles can be that way. And the policy fights are not limited to economics, but also reach into foreign policy and matters related to the defense of the nation.

Jack Kemp offers much in the way of campaign reporting on Kemp’s campaign for President in 1988 and his campaign to be Bob Dole’s Vice President in 1996. But compared to the policy battles of the day, the campaigns were given considerably less space.

One disappointment in Jack Kemp, is the lack of focus on Kemp’s work in what we would call “civil society,” though there are many differing views on what that actually refers to. Yes, there is an entire chapter titled “Poverty Warrior” which recounts Kemp’s years as Secretary of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). But this chapter really does not do justice to what Jack Kemp wanted and what he was actually fighting for.

During the years of the first Bush Administration, 1989 and 1993, there was only one point where a Kempian approach to things could have really changed perceptions and reality for President Bush. That point came in 1992 when Los Angeles erupted into riots after the Rodney King jury verdict. Jack Kemp was probably the last best hope to save the Bush administration and earn it a second term in office.

But, it was too late to save the Bush presidency. The work that Kemp had pursued could have changed history, had there been a more receptive audience, both in the White House and around the country. By the time the Bush administration cared about what Jack Kemp wanted to address, Bill Clinton had already told audiences he felt their pain, and he was on his way to unseating an incumbent President. The riots earned a mention on parts of 6 pages, total. For a book that consists of 327 pages of content, this is a real shame.

Jack Kemp spent plenty of time and political capital fighting for community-saving ideas like urban enterprise zones and parental choice in education. Kemp was indeed a “poverty warrior” wanting to offer a light at the end of the tunnel for those in the worst of despair, and refusing to turn his back on “the least of these.” Kemp saw economic growth as a vital element to turning the tide, or in the “rising tide” that would lift all boats. While he could be long-winded, as Kondracke and Barnes point out, and Kemp could talk more than some audiences were willing to listen, he never stopped believing in or advocating for economic growth as the ultimate solution.

The authors record their ultimate conclusion this way, “The full Kemp model—“bleeding heart” and “conservative”—is what the nation needs. Politicians who are principled, dynamic, positive, cheerful, inclusive, bipartisan, optimistic, unorthodox, disposed to compromise, committed to courting minorities, urban oriented, pro-growth, and antibureaucratic—and interested in ideas and action, not political tactics or personal attack. Idealistic. Visionary.”

We can quibble about these words until the end of time, and we probably will. Though it is hard to argue against them and remain true to them at the same time. But, the vision that a “Kemp model” (as the authors see it) offers, is the possibility of a return to greatness.

The reason to seek the “Kemp model” again now is rather simplistic in its nature, especially from a political point of view. In their interview with Norman Ornstein, he told the authors, “if Kemp had prevailed, we would be looking at a majority Republican party today” and they put forth, “because a Kempian GOP could win 40 to 50 percent of the Hispanic vote and 15 to 20 percent of the African American vote (versus 27 percent and 6 percent, respectively, for Mitt Romney in 2012).”

It is hard to argue against that math.

There are many reasons why the Kempiam model did not succeed in the ways that it could have. Some of these reasons are covered by Kondracke and Barnes, other reasons will have to wait. What Jack Kemp makes clear, is that it can be done. It just cannot be done alone. Whether is a single politician who takes up the mantle against the D.C. machine, or by a society that sends elected representatives to Washington and just hopes for the best. Jack Kemp needed Ronald Reagan, and vise versa. But even then, they were two men against the world.

What we need will require a team.

Leaders, whether church, business or political, cannot make themselves the things that make up the “Kemp model.” Not overnight anyway. But we can nurture these things in our young people and in our next generation of leaders. To not do this, to not pursue these ideals, is to witness more of the same that we have watched since the day Ronald Reagan boarded Marine One for the last time and waved goodbye.

The price for such inaction is way too high.

Finally, there is a Jack Kemp story beyond the Washington D.C. area code waiting to be told. That story will be told. This narrative is not offered in this noble work by Mort Kondracke and Fred Barnes, but this book is an important first work in the telling of the Jack Kemp story and I highly recommend it.

As the title states, Jack Kemp “changed America”, it was not the other way around. To see the real possibilities that America can achieve, start with Jack Kemp add some Ronald Reagan, and begin the real work from there.

Reaganomics and Arthur Laffer’s Supply-Side Wisdom

Review by Steve Parkhurst

“It should be known that at the beginning of the dynasty, taxation yields a large revenue from small assessments. At the end of the dynasty, taxation yields a small revenue from large assessments.”

Ibn Khaldun, a 14th century philosopher, may have been the first person to summarize supply-side economics, some 600 years before Congressman Jack Kemp’s Jobs Creation Act was introduced as legislation and supply-side economics was given its name.

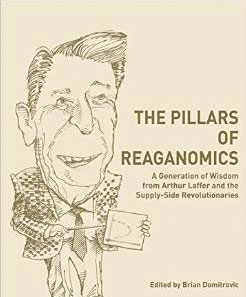

The Pillars of Reaganomics: A Generation of Wisdom from Arthur Laffer and the Supply-Side Revolutionaries, edited by Brian Domitrovic, represents a stellar addition to the supply-side economics library. What Brian Domitrovic has done here is he has taken monumental statements, monumental documents, and he has added some context and some history around them, and he has presented them in pretty much their entire original form.

This deeper, modern day context is really enlightening. And invaluable.

From a title that includes the word “pillars,” this book is exactly what you would expect it to be: Foundational documents that outline supply-side economics. What the title doesn’t tell you is that the commentary included in the book spans time from before Reaganomics (in the form of the Kemp-Roth tax bill), to the early days after passage and implementation, to the post-Reagan Presidency era of George H. W. Bush, Bill Clinton, and George W. Bush.

The content is most interesting because it is taken from papers prepared by Arthur Laffer or his staff from 1978 to the present. These papers consist of material not commercially available, even online in this day and age. I tried to Google some of the materials, and that proved a fools errand. For many years, other than in the Laffer archives, these papers may only be readily available because of the work of Brian Domitrovic in reproducing them.

The Pillars of Reaganomics includes original content from Arthur Laffer, Bruce Bartlett, Warren T. Brookes, George Gilder and Stuart Sweet. These writers, in the course of their scholarship, all offered great wisdom from others in the history of tax policy.

For example, Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon had this to say in his 1924 book, Taxation: The People’s Business:

“The history of taxation shows that taxes which are inherently excessive are not paid. The high rates inevitably put pressure upon the taxpayer to withdraw his capital from productive business and invest it in tax-exempt securities or to find other lawful methods of avoiding the realization of taxable income. The result is that the sources of taxation are drying up; wealth is failing to carry its share of the tax burden; and capital is being diverted into channels which yield neither revenue to the Government nor profit to the people.”

And there is this gem from Ludwig von Mises in his 1949 book, Human Action:

“Every specific tax, as well as the nation’s whole tax system, becomes self-defeating above a certain height of the rates.”

Somewhat billed as a “running commentary” of the supply-side revolution, this volume does prove to be a running commentary, but it’s also a historical document full of historical context. Even saying that could possibly do it injustice in the sense that this is not just commentary, it’s a substantive, well researched, well put together, contextual volume that helps relay what was happening, why it was happening, and how it was happening. This all plays out like a novel at times, even a novel where you know the end of the story, but you forgot about this person or that incident.

Any book about the Ronald Reagan presidency includes timeless quotes from the Gipper, and this book does not disappoint on that score. Bruce Bartlett recalls a classic early-1981 quote from President Reagan in describing the nations economy:

“There were always those who told us that taxes couldn’t be cut until spending was reduced. Well, you know, we can lecture our children about extravagance until we run out of voice and breath. Or we can cure their extravagance by simply reducing their allowance.”

And Milton Friedman wrote this in Newsweek in 1978 to make a similar point:

“I have concluded that the only effective way to restrain government spending is by limiting government’s explicit tax revenue – just as a limited income is the only effective restraint on any individual’s or family’s spending.”

Putting the sheer content of this volume aside for a moment The Pillars of Reaganomics is an outstanding addition to a library simply because of the work involved on the cover, which has an etching of a Ronald Reagan caricature holding a drawing of the Laffer Curve, and the interior of the book covers contain the tiled, gold-colored logo of The Laffer Center which published the book. This is just a really good physical object to hold and will make a great addition to the library of any Ronald Reagan fan or student of supply-side economics.

Because several authors are represented in this book, there are changes in style and wording, but that’s not only because of the writers involved, it’s because of the changes in our language over time. I found that refreshing.

The Pillars of Reaganomics serves as a great place to start an education on what supply-side economics is, how the concept was implemented in various decades, how the numbers stood the test of time, and how the world is looking at the economics policy now. This book is an enjoyable read, it’s not wonky. Let us hope there is more of this to come.

I will conclude this review with the words that open The Pillars of Reaganomics, on the dedication page, because after reading them, you may be as convinced as I was that this book, and potentially this series, is headed in the right direction:

In Memoriam Jack French Kemp.