Marco and Laura both pose a threat to southeast Texas, but each in a different way. To understand what’s happening with the two systems we need to first look at what was going on with March to see why the National Hurricane Center forecast initially said Southeast Texas impact, changed to a New Orleans landfall and now shows the storm skirting the coast.

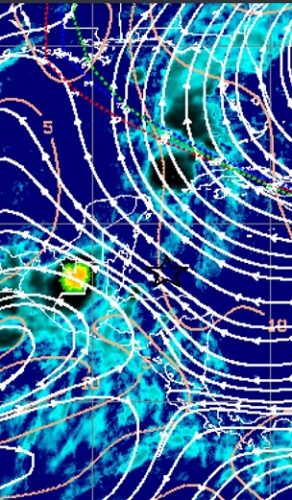

Back when Marco was in the northwest Caribbean Sea the original forecast was for the storm to head towards Houston. In the image below we see streamlines of the satellite derived steering currents. Marco was on the edge of a split in the steering currents. The initial forecast was for Marco to follow the currents to the northwest. Only Marco was too shallow and never was picked up by the northwest steering currents so continued on a more northerly direction and ended up being picked up by currents that were driving it northward and north-northwestward. (The star is the approximate location where Marco was located.)

Over time the steering pattern has changed a bit, and the slight change has important implications for the future track of March. I’ve been saying Marco will make a left (or west) turn, and we just have to wait and see when that happens. The model runs have been all over the place, so we need to see some run to run consistency before having much confidence in the results and forecast. However, the satellite derived steering is starting to shape up that the westward turn may be less far inland, or possibly offshore paralleling the coast.

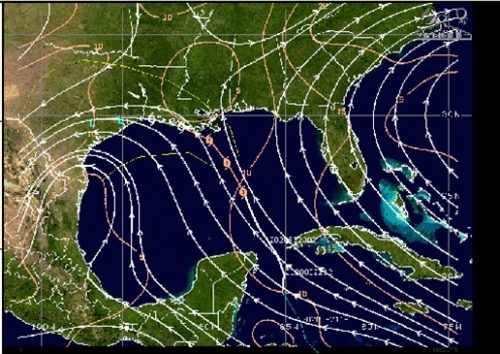

This morning two high pressure centers were present on the satellite derived winds, one over the Atlantic and one over Oklahoma. In between these two high pressure systems was a weakness in the high (or a trough if you must), and the forecast was for Marco to move inland into the weakness before finally making the left hand turn. (Note – the forecast path shown is for Laura.)

As the day progressed the satellite derived winds showed the same general pattern, but some subtle difference in the way the two high pressure systems were evolving lead to a significant change in when the left hand turn occurs. The high over the Atlantic is ridging farther westward, and the high that was in Oklahoma has moved westward. The high in the Atlantic is nosing in under the weakness/trough between the two leaving that void less influential. A weak area of mid-upper low pressure in the far western Gulf of Mexico is now more influential and imposing a westward flow. As a result the models are saying that the westward turn will happen just barely inland, or possibly even offshore.

Now, that’s all fine and dandy, but is this actually showing up with Marco? Not yet, but satellite imagery is suggesting that the impacts are starting to be felt. The animated GIF is too large to fit into the blog, but the clouds to the west of Marco are starting to show evidence of being impacted by the mid-upper low. Looping visible satellite imagery at last light shows high clouds on top of the lower clouds moving in a northerly direction. This holds true throughout the loop, however, the lower clouds direction changes. At the beginning of the loop they were moving southwest. As the loop progresses the motion changes to more of a westward motion showing that the mid-upper low is exerting more influence. This is important for two reasons. First, it will mean there’s a more westward component to the steering, but also as the low continues to retrograde to the west heights will rise in the low’s wake and tend to impart a more westward motion on Marco. We will have to wait and see if this holds up, and when the westward turn occurs, but as of now there’s some support for the shift in model output.

What does this mean for Southeast Texas? If you are east of Harris County, it’s actually not bad news. Because of the curvature of the land this is not a bad scenario. If Marco moves inland before turning west then he will weaken over land and bring rain, but not much else. If the turn occurs offshore areas east of Harris County are farther north because of the way the land curves and it will be more of a near miss than a direct hit. This would be more impacts than if Marco moves inland before turning westward, but the strongest winds and rain would move south of the area in the Gulf. For Houston, it’s more of a hit or miss event. Just like with areas east of Harris County, if Marco moves inland first then the impacts will be rain and not much else. However, just like the land curvature helped the areas to the east it hurts Houston. The land curvature is such that if the westward turn occurs just offshore Galveston or Fort Bend Counties could be in the potential landfall areas. Now, the storm could turn even a little quicker and have landfall farther to the southwest. However even a landfall in Galveston of Fort Bend Counties would likely be as a tropical storm because the storm will be moving into an area of higher wind shear which will cause weakening regardless of if the storm is over land or not. Almost all the intensity guidance shows weakening to a middling tropical storm status even if the system stays offshore until reaching landfall in Texas. This is not ideal, but not a devastating scenario. Wind, rain, a bit of storm surge. Not devastating, not Harvey or Imelda, but unpleasant.

Laura also poses a potential threat, but we would need to see how she fares with the interaction with Cuba before really getting a handle on the potential impacts. The steering would be a matter of how far does the high from the Atlantic expand westward. The models have been moving westward, but now seem to have stopped the westward expansion. Let’s get through Marco, and see how Laura handles interacting with Cuba before worrying. We have plenty of time to prepare if Laura does come this way. Right now, it looks to be more of a threat to the triangle and Southwest Louisiana, but we really won’t have a good fix until she is in the Gulf.

Be prudent, but don’t panic. Marco may be a threat, but it’s not a danger. Laura could be more serious, but we are a long way from knowing how much of a threat she may be.

Streamline images courtesy of University of Wisconsin CIMSS.